"This must come to an end"

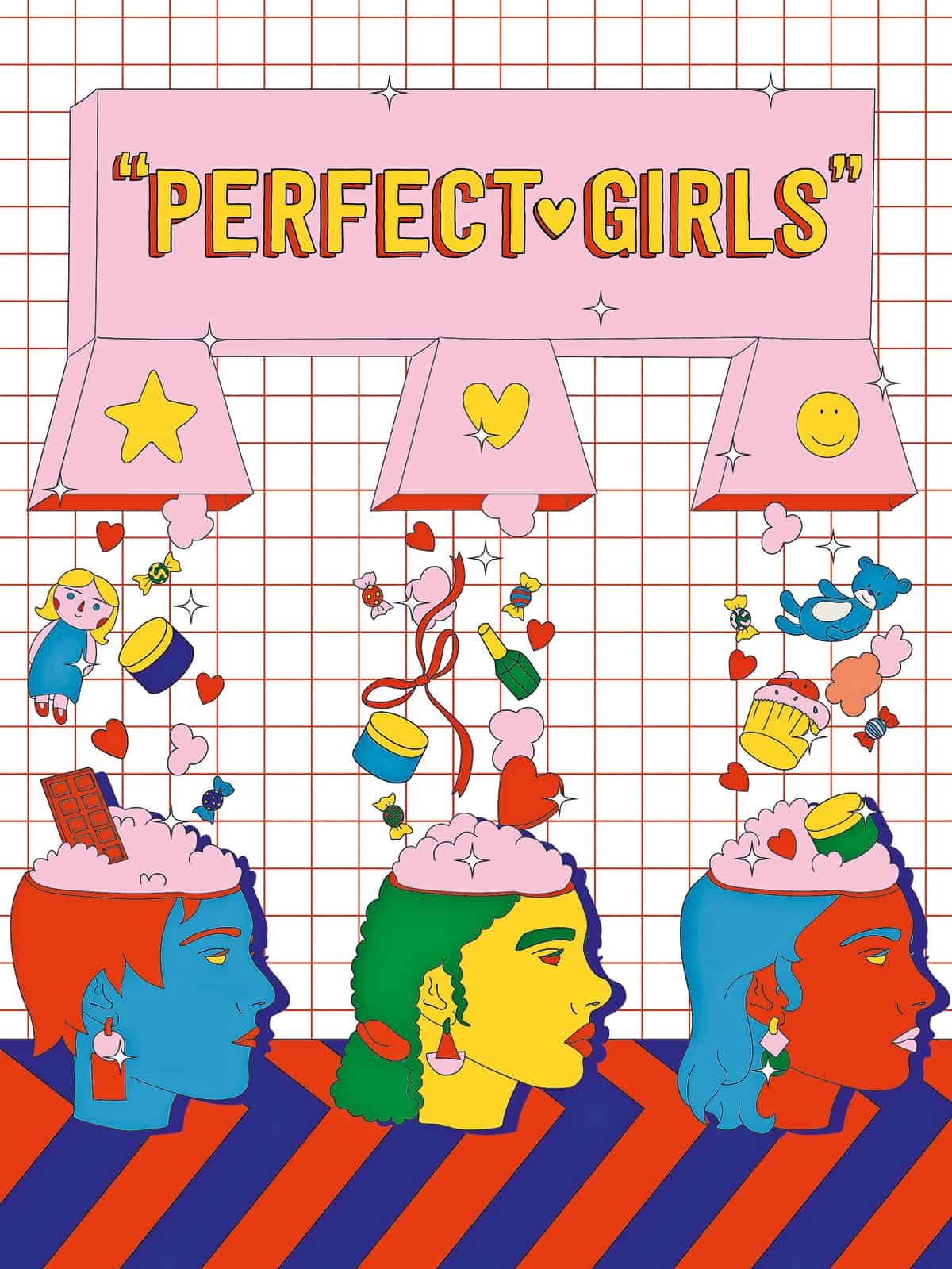

First, advertising told women to be more beautiful, slimmer, younger. Then it tried to sell them inauthentic "fempowerment." Enough is enough, say bestselling authors Jane Cunningham and Philippa Roberts.

m&kWith "Brandsplaining" you wrote a bestseller about the - often problematic - image of women in marketing and advertising. Why was the time ripe for your book?

The harmful narratives remain, only you recognize them at second or third glance.

Roberts: Exactly. In our book, we refer to this as "sneaky sexism." Another example of the same would be the use of symbols or color codes that predate modern discourses of equality. Whereas packaging used to say "For Him" or "For Her," companies now simply use the softer, gentler, weaker colors for women. And more floral decorations. Men's packaging, on the other hand, features the dark, bold, striking colors. Sporty patterns, typography that signals movement and strength. The same thing is communicated as before, just in subtext.

Where does this basic tenor in marketing and advertising - which you mentioned earlier - come from, which demands that women constantly work on themselves, constantly "improve" themselves?

Roberts: The roots of this lie deep in our social and cultural history. Throughout the millennia, women have actually always had a secondary status socially; this implied that they had to behave and present themselves in such a way that they were pleasing to men. Their job was merely to secure male approval. And, you know - we as a modern society like to talk about how much has been done in terms of equality in politics and in business. But the reality is that the vast majority of CEOs are still men, and the vast majority of heads of state are also men. The reality is that men still hold the power in many places; alone bear the responsibility. Consequently, women are still often expected to behave in ways that do not upset the powerful.

... which is reflected in the ideals conveyed by marketing and advertising ...

Roberts: Yes, little girls should be cute and sweet, take care of animals and dolls, find everything nice that is pink or pastel, while little boys are allowed to experience adventures. It doesn't matter if they get dirty, if they are bullies. Girls, on the other hand, are permanently and practically from the beginning of their lives exposed to messages that they have to look better, "be" better; they are totally reduced to their appearance.

Cunningham: The latter, by the way, is something that gets worse when the girls become young women. Do you remember the Victoria's Secret fashion shows? There used to be these very young models who were all over the media - talking about how much weight they had lost, how much exercise they did to get even thinner, they had hair extensions done, et cetera. Then they got on the catwalk wearing huge wings. They were angels, portraying a cliché that said, "I'm here to be as beautiful and as appealing as possible - not to myself, but to the male eye." And of course, the prettiest, slimmest, bustiest angel got to wear the white wedding lingerie at the end of the show. The message was, "Make an effort and optimize yourself, then with luck you may get married someday!" (laughs)

Roberts: Mothers, too, are constantly suggested that they have to be perfect, which in turn implies that they fail if they're not ... if they're not happy about being a mother one hundred percent of the time. And older women, we've talked about this before, just disappear from the scene because they're no longer ... "useful" when viewed through a male lens. You know, it's not just in marketing, it's a cultural problem in general that these ideas about women are still being conveyed. But while we're finally seeing progress in film, music, and television programming, marketing and advertising are really lagging behind.

"The prettiest, slimmest angel gets to wear the wedding lingerie at the end. The message: if you make an effort, you might find a husband someday."

Do you have any idea why that is? In general, after all, marketing and advertising professionals see themselves as people who not only recognize trends, but actually set them ...

Roberts: One of the very immediate reasons is certainly that the creative departments in agencies are still largely staffed and run by men. I don't know about you in Switzerland, but here in London, about two-thirds of the people who work in creative departments and create campaigns are men. And also a certain kind of men: quite young, usually white, usually more urban socialized. The culture there is often this "Hey, bro!", this emphatically casual display of masculinity. These creatives tend to care more about a good punchline than about really and deeply understanding their audience. Fittingly, there's also a big pay gap of about thirty percent between male and female employees in the agencies - which is pretty hypocritical, since the agencies are selling empowerment communications but not living up to their own standards at all.

You talked earlier about the data you've collected. Agencies and marketing departments tell me all the time that they, too, make their decisions based on data. But if they really did that, they would have to treat female audiences differently, right?

Cunningham: Well, the relevant agencies and big companies collect a lot of data, yes. But when they do market research themselves, they often ask the wrong questions. They go to a group of women and say, "Would you like bullshit innovation number one or bullshit innovation number two?" And even though neither option is really attractive to the focus group, the women are likely to answer, "If we have to choose, we'll just choose number two." And the company concludes, "Great, we evaluated that, they think number two is great." But what wasn't asked is, "How do you feel about our bullshit in principle?" There, the answer would probably have been quite different (laughs).

What should change here?

Cunningham: It should become standard practice to ask women openly and honestly for their opinions. For example, "What don't you like about the way this brand addresses you?" Or, "Which of your needs are not being met by this product?" Again, yes, there's plenty of data to go around. Yes, there's a lot of research being done. But how much of it is real listening, how much of it is an effort to have a real dialogue? The kind of dialogue where companies are totally open to the answers they get? In our consulting work, we've heard over and over again from clients, "Yeah, we talked to a focus group, but they just said the things that women just always say." Well, if they say something over and over again, maybe they mean it! (laughs) How absurd to use that as an argument for not giving meaning to a statement, right?

Roberts: Sometimes there's also this sexist undertone where marketing or advertising executives say, "Oh, I'm not going to let six housewives interviewed somewhere tell me what my advertising should look like ..." To these guys, it may sound plausible and tough in a meeting, but in reality it's very demeaning, condescending and ensures that important messages are not heard.

"The reality is that men still hold the power in many places; are solely in charge."

And they need to be heard, you say, even if they are inconvenient for companies.

Roberts: Of course, it is never easy for a company to hear that its female customers are dissatisfied; of course, it is difficult to face up to uncomfortable truths. Especially when the insights gained mean that you have to change a lot. But we always say that change is coming anyway - the "tipping point" is here, marketing and advertising must finally take this fact into account. We are in the midst of a massive cultural shift because women are better educated than ever before. Because through social media, which otherwise definitely has its drawbacks, female voices - and voices that deviate from the mainstream - are being heard.

Cunningham: Women cannot and will not be silenced any longer. So the time is ripe for better marketing, better advertising. Hence our book, which carries an important message: If brands and companies are serious about appealing to women, attracting female customers and retaining the female customers they have, they need to move. Immediately. We are witnessing the dawn of real, authentic "empowerment" - as opposed to the superficial narratives that have circulated over the past few years.

"Women can't and won't be silenced anymore. So the time is ripe for better marketing, better advertising."

You would have to explain that to me again in detail, please.

Roberts: The false, superficial "fempowerment" narrative has continued to suggest to women that they should change, but targeted their inner attitudes in the process. Brands used to proclaim messages like, "You need to optimize your looks." Then they moved to saying, "You need to optimize how you act, think and feel." Women are supposed to be career-driven, fearless. Bold. "Strong is the new beautiful." "Fempowerment" understood in this way has no interest in eliminating the system and the stubborn remnants of patriarchy, but continues to locate all the responsibility on women. And actually, that's exactly what needs to stop.

Entrepreneurs may wonder what will happen to their sales if they can no longer claim that their products are necessary for a better life.

Cunningham: There's nothing wrong with meeting needs, is there? There is absolutely nothing wrong with satisfying needs and asking women what they want in order to then develop helpful products and services. What is wrong, however, is this hyper-critical view of women that says, "There's something wrong with you. We're going to make you feel like there's something wrong with you. So that you think you need a remedy for it. And then we will sell you that remedy. Therein lies the great cynicism.

What can men - in marketing and advertising, but also beyond - do to help drive positive change?

Roberts: I think the most important thing is first to become aware of problematic narratives. This age-old idea of a "woman who must please" is so firmly etched into the collective consciousness that it still influences how audiences are segmented, categories are codified, communications are produced, and proposals are written. Men need to understand this and be attentive and critical from it. Fortunately, this is where knowledge makes a difference: once you start to deal with it, it's virtually impossible to return to a state of ignorance.

Jane Cunningham and Philippa Roberts are founders and managing directors of the Consultancy "Pretty Little Head, which advises companies on marketing to female audiences. As part of their work, they have authored several international studies and three books. Previously, they worked in the agency industry, for example at DDB and Ogilvy.